From Alpine cellars to Amarone casks, a new generation of distillers is redefining what whisky can be—through an unmistakably Italian lens.

Italian whisky is no longer an oxymoron. What once sounded like a contradiction now reads as an emerging category, quietly serious, culturally grounded, and increasingly validated on the world stage. Rooted in centuries of distilling expertise and shaped by Italy’s singular relationship with wood, climate, and craftsmanship, a small but growing number of producers are proving that whisky, too, can speak fluent Italian.

Recognition has come swiftly. One of the country’s most respected grappa houses, Poli Distillerie, has become the first Italian whisky maker to earn accolades at the International Spirits Challenge in London, among the longest-running and most prestigious spirits competitions globally, as well as at the Falstaff Italia awards. Its Segretario di Stato and Conclave whiskies received bronze and silver medals, marking a decisive moment for the category.

“When we approached the world of whisky eleven years ago, it was a stimulating challenge, not only from a production perspective, but also from a cultural one,” says Jacopo Poli, owner of Poli Distillerie. “We were entering a fascinating yet completely new universe, with humility and respect.”

That humility is central to the Italian approach. Rather than attempting to replicate Scotch, Italian producers have leaned into their own distilling heritage, particularly the technical mastery developed through grappa production. Bain-marie pot stills, precise temperature control, and an instinctive understanding of wood define whiskies that privilege elegance over force, texture over power.

“Our whiskies, and Italian whiskies in general, though of recent genesis, convey a precise and defined identity,” Poli explains. “They are rooted in a centuries-old distilling tradition—grappa distillation, which today finds new ways of telling the story of our territory and our vision of elegance.”

Sacred Names, Secular Precision

Segretario di Stato whisky was created to commemorate a specific moment in Italian history: the October 15, 2013, appointment of Cardinal Pietro Parolin as Secretary of State of the Holy See. Parolin is the most illustrious citizen of Schiavon, the small Veneto town that has been home to Poli Distillerie since 1898. The whisky itself is a single malt, gently peated, distilled artisanally in a bain-marie pot still, aged for five years in oak, and finished in Amarone casks, an international spirit with a distinctly Venetian soul.

Conclave whisky takes its name from the Latin cum clave, meaning “room closed with a key,” referencing both the sealed chambers in which cardinals elect a pope and the locked casks in which the whisky matures. Produced from both peated and unpeated malted barley, distilled separately, the spirit rests in medium-toasted white oak barrels that have been used and regenerated, allowing only the softest tannins to emerge. After five years, individual barriques are blended into a whisky described as “bold and vibrant, evoking the ritual of waiting.”

A National Movement Takes Shape

Italy today counts roughly a dozen whisky distilleries, each shaped by local terroir and traditions.

In Sardinia, Silvio Carta Winery works exclusively with barley grown on the island, aging whisky in chestnut barrels that once held Vernaccia di Oristano. In Tuscany, Winestillery matures its spirits in Super Tuscan and Vin Santo casks sourced from its sister winery in the heart of Chianti Classico.

High in the Dolomites, the Dolzan family’s Villa de Varda produces its InQuota mountain whiskies using water from the Brenta mountains, including an expression aged in spruce, an unmistakably Alpine interpretation.

Italy’s first dedicated whisky distillery was founded in 2010 in Glorenza, in Alto Adige, by the Ebensperger family. “We call it the Italian Highlands,” says architect and builder Albrecht Ebensperger. Whisky here is produced underground using traditional Scottish Rothes stills, with overheated water replacing steam for precise temperature control.

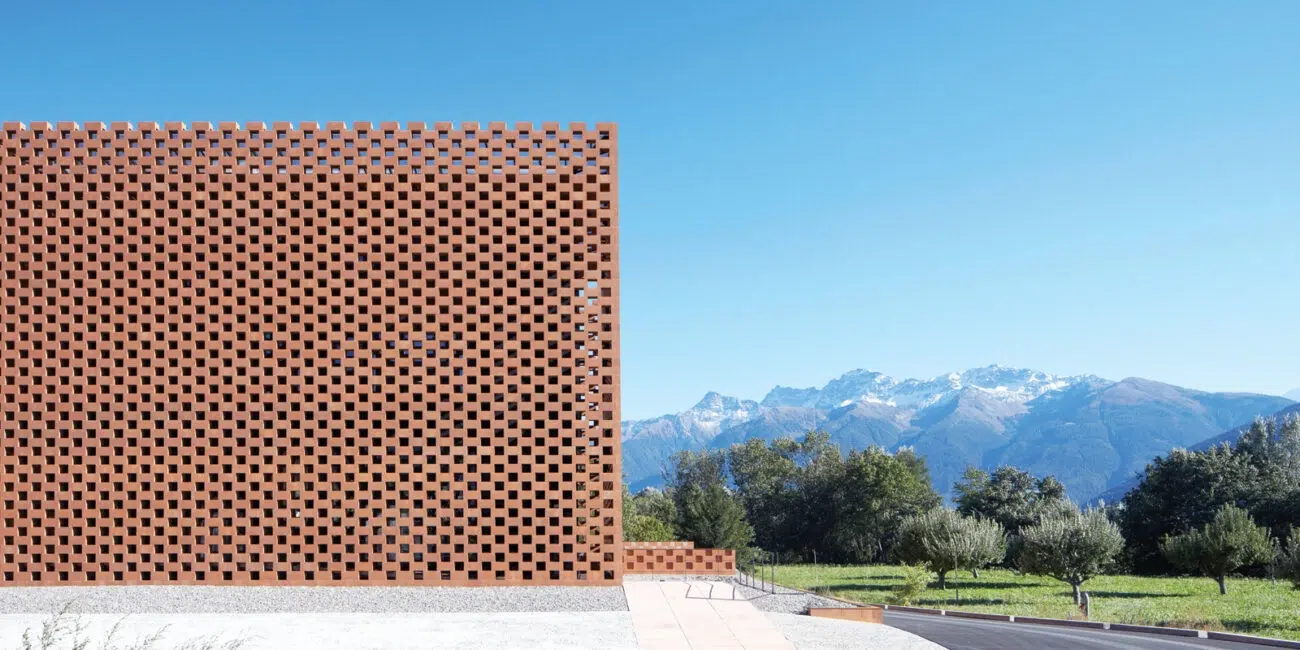

The distillery, Puni Distillery, is housed in a striking 13-meter-high cube designed by Werner Tscholl, a tribute to local barn architecture. Bottles designed by Christian Zanzotti echo the same minimalist rigor. Puni, named for the local river, benefits from warm summers and cold winters that accelerate maturation. The range includes Nova, Alba, Sole, Nero, and Vina Puni, each defined by distinct cask regimes spanning American oak, Marsala, Islay, Pedro Ximénez, and Pinot Noir barrels.

Further south, in Tramin, home to the Gewürztraminer grape, Psenner Distillery produces eRètico, Italy’s first single malt from the region. Distilled using Bavarian malted barley, the whisky matures first in ex-grappa French oak casks sourced from Armagnac, then briefly in Oloroso Sherry before returning to grappa wood, a uniquely Italian aging cycle.

Italy and Whisky: A Long Affair

Italy’s relationship with whisky long predates domestic production. The country became the third-largest importer of Scotch in the mid-1970s and the world’s leading market for single malts. Genoese firms such as Wax & Vitale were importing whisky as early as 1906, while Italians were exporting their own “Whisky Italiano” and even “Whischy Medicinal” to the United States during Prohibition.

Following World War II, Allied troops reintroduced whisky to Italy, where it was embraced as a symbol of la dolce vita. The opening of Edoardo Giaccone’s whisky shop in Salò in 1959 cemented Italy’s role as a global whisky capital. By 1979, Scotch imports had reached 40 million liters.

Collectors followed. Bottlers such as Silvano Samaroli collaborated with Cadenhead and Gordon & MacPhail, while High Spirits in Rimini released beautifully labeled single casks. Whisky was collected as much as it was consumed. Giuseppe Begnoni later acquired Giaccone’s legendary collection, the largest in the world at the time.

Today, Italy still drinks more Scotch per capita than the United States. Milan has hosted an annual whisky festival for more than two decades.

“Whisky remains a niche passion,” says Luca Chichizola, former Italian ‘Whisky Maniac’ and now brand ambassador for Rossi & Rossi and its Scottish bottling arm Wilson & Morgan. “But if you have a strong wine culture, it’s easy to appreciate good spirits. There has always been a fascination among Italians with the refinement and tradition of British luxury products.”

Founded by Mario Rossi, who discovered whisky through friendships with English soldiers during the war, Rossi & Rossi was a key importer of official distillery bottlings in the 1970s and ’80s. Today, under the direction of Fabio Rossi, the company continues to source and mature stock in bonded warehouses across Scotland.

A Distinctly Italian Expression

Italian whisky is not attempting to compete with Scotch on its own terms. Instead, it offers something more nuanced: spirits shaped by wine culture, Alpine climates, historic distilling knowledge, and an instinctive sense of balance.

It is whisky interpreted through Italian sensibility, measured, architectural, and expressive without excess. And increasingly, it is being taken seriously.

Not as an exception.

But as a category coming into its own.