The father of vodka has returned. Behind this revival stands a graduate of John F. Kennedy Catholic High School in Seattle, Washington, who transformed a forgotten tradition into a modern renaissance.

The Resurrection of Polugar

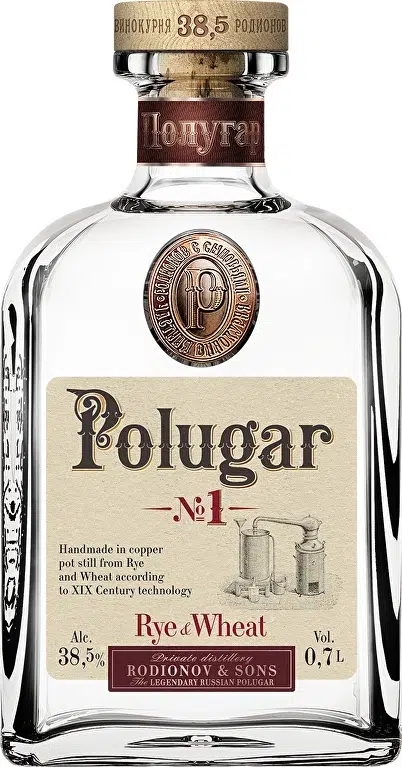

Polugar, the original vodka, predates the drink we know today. Thanks to Rodionov and Sons, a private family distillery in Poland near the Russian border, this lost bread wine has reclaimed its place among the world’s noble spirits.

Vodka only became vodka—literally “little water”—in 1867. Until then, Russians raised glasses of bread wine. “That transformation happened when the French invented rectification towers,” explains vodka historian Alexey Rodionov, who now runs the distillery with his father Boris and brother Ilya. “Before that, Tsars, Tsarinas, and Peter the Great all drank Polugar.”

Unlike modern vodka, Polugar is distilled in copper stills and clarified with natural methods. Moreover, Alexey’s father reconstructed the stills using 18th-century blueprints, ensuring every detail preserved the original flavor profile.

Bread Wine: Russia’s True Heritage

The first written mention of distilled spirits—or “hot wine”—appears in 1515 in a monk’s letter. Later, vodka was even applied as an antiseptic on King Vasily III, father of Ivan the Terrible, though without success. By 1895, however, Russia enforced a state monopoly, destroyed copper stills, and prohibited Polugar production. Vodka, stripped of complexity, became the national standard.

Because Russian law still forbids traditional grain distillation, the Rodionovs craft Polugar in Poland. Their restored Łódź distillery not only revives old methods but also honors forgotten flavors.

“Our Polugar replicates the taste of the 18th century,” Alexey says. “Back then, instead of aging in oak, noble families clarified with egg white to preserve the raw character of the grain.”

Today, celebrated bartenders such as Simon Caporale, Salvatore Calabrese, Mariam Beke, and Leonardo Leuci are rediscovering Polugar’s unique depth.

A Spirit With Story and Soul

The very name Polugar means half-burned. Before alcohol meters, distillers measured strength by burning off half the liquid. If half remained, it was Polugar.

Alexey’s father, a retired scientist, uncovered 18th-century recipes that revealed more than 300 varieties of bread wine—from garlic-spiced infusions for night guards to romantic blends for lovers. “Recovering those formulas took years,” he reflects, “but the results exceeded every expectation.”

Today, the Rodionovs compare Polugar more to whisky than vodka. Using rye and water, they triple-distil it in reconstructed copper pot stills, then refine the spirit with birch coal and egg white. The result is a layered, elegant drink with heritage in every sip.

Restoring National Pride

“Bread wine doesn’t exist in modern Russian documentation,” Alexey notes. “That means we can’t license it at home. Still, Polugar is Russia’s true national drink. It belongs alongside whisky and brandy.”

For their Connoisseurs Range, the Rodionovs distil single grains. Their Mixology & Gastronomy line introduces natural infusions during the third distillation, echoing recipes once served at aristocratic feasts. Each bottle is modeled after the 1745 vessel of Queen Elizabeth, daughter of Peter the Great—an original preserved in the Russian National Museum.

In old Russia, every meal featured seven or eight courses, each paired with a different bread wine. Pork came with garlic, herring with caraway, and dumplings with dill. Today, Polugar revives this tradition with rye, wheat, barley, buckwheat, garlic and pepper, cherry, horseradish, honey, and more—each bottled at 38.5% ABV.

Once dismissed, the distillery now produces 100,000 bottles annually. “Russia’s oldest drink,” Alexey says with pride, “has become one of America’s newest discoveries.”

Potocki: Polish Elegance in a Glass

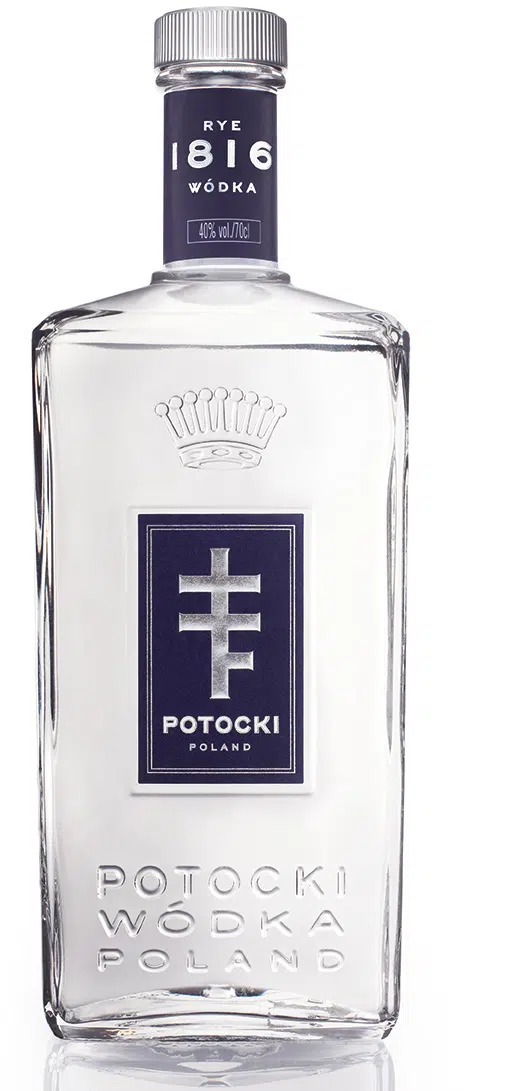

If Polugar represents Russia’s lost legacy, Potocki Vodka embodies Poland’s aristocratic refinement. Founded in 1784, the Łańcut distillery entered the Potocki family in 1817 and produced premium vodka for generations before closing in 2021. Today, Jan-Roman Potocki has restored its legacy.

Each white flint bottle carries the Pilawa coat of arms, the insignia of Poland’s szlachta nobility, along with the hunting mark of Jan-Roman’s great-grandfather. The distillery’s history is storied: it once produced colognes and liqueurs, and its flavored vodkas won gold at the 1816 Paris Fair.

Now distilled in central Poland, Potocki remains resolutely artisanal. “We use only superior rye from the surrounding fields,” Jan-Roman explains. “The mash is distilled twice at low speed, which maintains balance and smoothness. We deliberately avoid charcoal filtration to protect the natural flavor.”

Global Recognition

Today, Potocki is served at the world’s finest destinations: Mandarin Landmark Hong Kong, Duke’s London, and the Raffles Europejski Warsaw Long Bar. Its versatility shines whether sipped neat, paired with vermouth, or accented with lemon.

Acclaimed mixologist Jerri Banks has created bespoke cocktails such as the Crimean Sonnet (vodka, blackcurrant juice, plum preserves, pepper), the Mirage (agave syrup, jalapeño, cilantro, lime), and the savory Hetman (beef consommé, celery seeds, horseradish).

Jan-Roman’s personal favorite, The Skylark, balances elegance and freshness:

-

2 oz Potocki Vodka

-

5–8 fresh grape tomatoes

-

4 basil leaves

-

2 drops aged balsamic vinegar

A modern cocktail where Polish present meets Polish past.

Heritage Reclaimed

Together, Polugar and Potocki represent two extraordinary revivals: one resurrects Russia’s forgotten bread wine, the other sustains Poland’s aristocratic vodka lineage. Both stand not only as exceptional spirits but as cultural ambassadors—worthy of sharing the same stage as fine whiskies, cognacs, and wines.